Houston, we have a (minor) problem...

As any full time physicist will tell you, building a cosmic ray detector isn't easy. We've had quite a few setbacks over the last 2 years, but so far we've managed to overcome all of them. As a development team we've been focused on for the last 6 months on delivery - getting all the individual components designed, tested, manufactured and assembled into the first batch of 31 boxes that are now either on their way, or already connected, at schools across the world. These are the lucky teams who were awarded a Cosmic Pi as a prize in the CERN Beamlines for schools competition 2016. Now that we have units that have been functionally tested, we've started to dig a little deeper into the operation of the device to try and make improvements, which will be available through firmware (the software which runs on the Arduino inside the Cosmic Pi box) updates. This post describes what we've been working on in the last two weeks and the problems we've found and the solutions we're working on!

When we tested the units before shipping, we ran through a series of 'production' tests designed to verify the electrical integrity and functionality of the unit. If you have a unit, you can view it's production test here. The production test is, in effect, a check-out for each individual system of the Cosmic Pi. If all the systems are working, we consider the device operational. One thing which wasn't included in the production test was a verification that the rate of muon detection conforms to the accepted figure of merit for Muon flux at sea level of 1 muon/cm2/minute. The actual figure for our detection of muons will be lower, since Cosmic Pi isn't an ideal detector. However, the more observant of you may have noticed that the typical event rate for the units which have been shipped is in excess of 1.2 events per second. This is a clue that something isn't working correctly!

So what are the extra events?

This is something we're in the process of working out. There are several candidates:

- Electronic noise - spurious signals caused by electrons in the wrong place

- Gamma rays - which may also deposit energy in the scintillator, of either terrestrial or extraterrestrial origin.

- Something else - highly unlikely, since full time Physics researchers have been doing this kind of experiment for quite a while and haven't yet discovered any non-Standard model particles acting in this way.

Right now, we're working on reducing the electronic noise. We're also calculating the energy deposited by various types of particle in the scintillator to see what the resulting light yield should be. But first, here's another useful test you can only do with 2 Cosmic Pi's...

Surely some coincidence?

A basic test to validate the functionality of the detection of cosmic origin muons is to sit two units on top of each other and check that (to a reasonable degree of accuracy) they record the same muon passing through each of the scintillator slabs at more or less the same time. Since muons are predominantly of cosmic origin and travel vertically downwards, there should be good agreement between the two readings. Having performed this experiment with two randomly selected remaining units, we got a coincidence rate of less than 3% with a fairly wide time threshold for overlap. This is a rather clear indication (together with the elevated rate) that something is wrong and that we're picking up either noise or some other particles which do not move vertically down as we expect the cosmic muons to do. This leads us to the more basic question, does it even work at all?

Fortunately, it does work.

Being based at CERN, it's a lot easier for us to get access to professional scientific equipment than people who don't have the good fortune to work in a research institute. With the help of the Beamlines for Schools team, we were able to get hold of two scintillator paddles (each one has an area of about 25 cm by 25 cm), Photo-Multiplier Tubes and NIM crate with the necessary drive electronics. By overlapping the two large scintillators (which we know are sensitive to muons) and triggering a counter on coincidences - i.e. when a particle is seen by both sensors within a window of a few nano seconds, we can quickly build a high efficiency cosmic ray detector. We can then adjust the area of overlap of the two scintillators to match the 65 mm x 65 mm scintillator of the Cosmic Pi, which we can also put in between the two plates since it's nice and small.

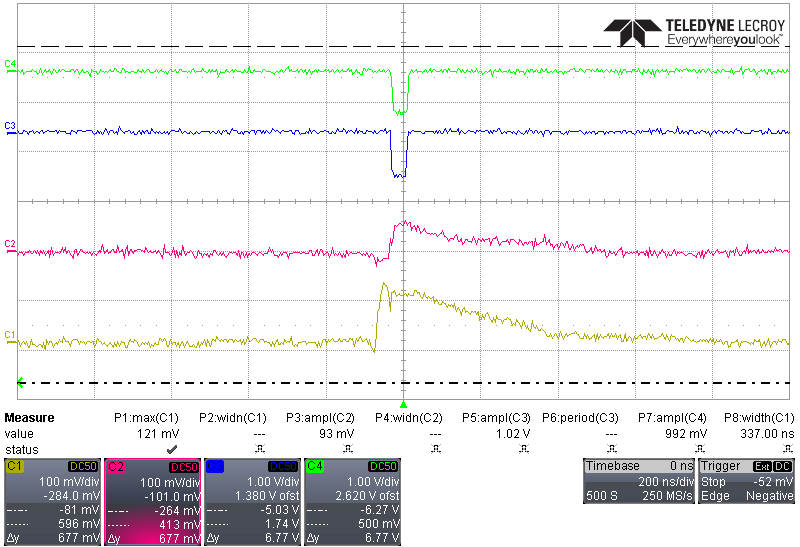

By doing this we've constructed a great way to test IF the Cosmic Pi is detecting muons. The oscilloscope trace above shows the output signals from the two large scintillators (channels 3 and 4, where the dip in voltage indicates detection of a Muon on each channel). At the bottom of the trace, you can see channels 1 and 2 showing the signal output from the two Silicon PhotoMultipliers on the Cosmic Pi unit. This required the disassembly of the unit and some additional soldering, so it isn't recommended for Cosmic Pi recipients, but we're also working on some new firmware to create a 'virtual oscilloscope' so that disassembly and soldering won't be necessary to see things like the above trace. The two simultaneous peaks in channels 1 and 2 show that the muon (at this point it's a confident assumption) passed through both external scintillator plates and (from channels 3 and 4) the Cosmic Pi scintillator, leaving a detectable signal in both systems.

So you found one muon, is that everything?

The above scope trace is a great confirmation that Cosmic Pi works in reality, not just on paper. However, we've still got our work cut out improving the detector. The detection mechanism has a couple of stages which are interrelated and therefore complex to tune. If you take a look at slide 12 in this presentation given at ORCONF 2015, you can see the two variable threshold discriminators which form the main parts of the trigger system. In order to make the event light flash on the front of the Cosmic Pi box we need to go through the following stages:

- Set up the bias voltage on the SiPMs - this is very sensitive and temperature dependent (so needs to be re-adjusted in time)

- Set up a threshold value for each SiPM, which has to be carefully selected to cut out the electronic noise

- Check that the rate isn't too high (noise saturation) or too low (insufficient bias voltage on the SiPMs, or another problem), and adjust the bias voltage, thresholds or both of them

This is complicated because the first two parts are highly interrelated, especially when using the count rate as the measure of how well or badly everything is set up. One of the things we've been looking at is how we can confirm the thresholds set for detection, relative to the shape and magnitude of the waveforms coming from the SiPMs, and to this end we've produced a little Arduino sketch that can replace the main Cosmic Pi firmware to verify the operation of the threshold setting process (if you do try this out, make sure to restore the original firmware when you've finished!). Over the next few days and weeks we'll add this process to the main Arduino code in order to improve the detector operation, with the aim of catching all the coincidences and removing as many spurious events as possible.

The next stages of development

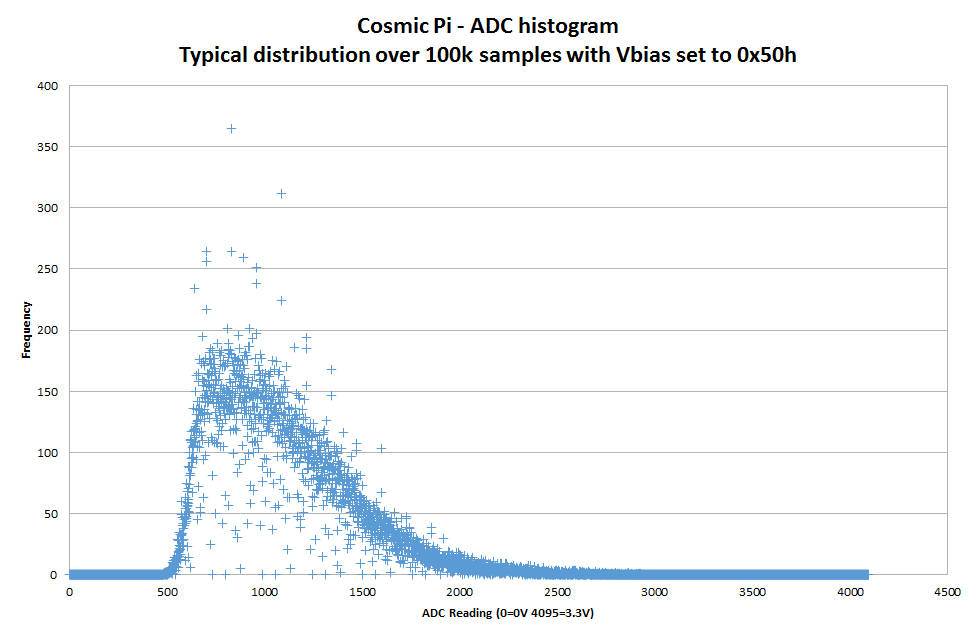

Our next development goal is to improve our auto-setting functions for the bias voltage and thresholds. Doing this should reduce the detection rate as we cut down the background noise, and improve the probability of being able to detect coincidence between two individual Cosmic Pi units. The histogram above shows the profile of the incoming signal we measure, most of which is noise, with some signal elements above about 1500. We'll be testing the accuracy of our improved software in between the two large scintillator paddles to ensure that we have an external check that it actually was a muon.

Taking a detailed look at the data

In an ideal world the plot above would show several discrete peaks in the centre region, each one indicating a number of photo-electrons. One photo-electron corresponds to the minimum sensitivity of the SiPM device, if one photon hits the sensor it produces a signal. If two photons hit the sensor it produces a proportionally larger signal, the same for three photons etc. The source of most of these photons is thermal noise within the device or the sensor itself. This means that the frequency of the noise is inversely proportional to the magnitude - lots of noise events can be expected at one photo-electron, and many fewer at 10 photo-electrons. This fits broadly with the shape of the above curve. It also tells us that the signal we get from muons in the scintillator is not particularly strong, however this may just be a function of the applied bias voltage at which the curve was measured (we'll be scanning this to make sure). It does also mean that we can still detect muons through the use of coincidence between the two SiPM sensors, since the probability of two large magnitude noise events occurring on both channels within a few nano seconds is very small.

If you have received a Cosmic Pi and want to get involved in helping us make it better, you can start looking at (and compiling your own versions of) our source code from github.com/cosmicpi where the device firmware is in the -arduino branch.

Muons are hard to catch, is there anything easier we can do?

It's also worth noting that the Cosmic Pi doesn't just detect cosmic rays. Within the box are the following additional sensors:

- 3 Axis accelerometer, which can be used for everything from checking which way up the box is facing, to detecting earthquakes.

- 3 Axis magnetometer, which can be used as a compass and for detecting changes in the magnetic field around the box.

- A MEMS Barometer, which can tell you the altitude and atmospheric pressure.

- A GPS receiver, which will tell you the time and position of the box, as well as it's velocity when moving. The GPS receiver can also tell you which GPS satellites are overhead if you ask nicely, and how strongly they are being received.

- A temperature and humidity sensor, which tells the temperature and humidity within the box. These are probably correlated to the temperature and humidity outside the box, but we haven't had time to study that yet.

If you want to take a look at these output signals, a full explanation of the command line device output can be found here. There's a lot of opportunities for all kinds of scientific projects with the hardware we've built - but for now we're focusing on revising the Arduino programming to detect as many muons as possible! You can find instructions to flash the latest firmware to your Cosmic Pi here.